What is fluorescence?

Fluorescence, a Chinese term also written as “yingguang,” refers to a cold luminescent phenomenon in which a substance emits light upon being excited by incident light of a certain wavelength—typically ultraviolet or X-ray. When a substance at room temperature absorbs energy from such incident light, it enters an excited state and then immediately de-excites, emitting light at a longer wavelength than that of the incident light (usually within the visible spectrum). For many fluorescent substances, the emission ceases immediately once the incident light is removed. The emitted light with these characteristics is called fluorescence. Additionally, some substances continue to emit light for a relatively long time even after the incident light has been turned off; this phenomenon is known as phosphorescence. In everyday life, people often broadly refer to any faint glow as fluorescence without carefully examining or distinguishing the underlying mechanisms responsible for the luminescence. It also refers to cool light with a low temperature (not color temperature).

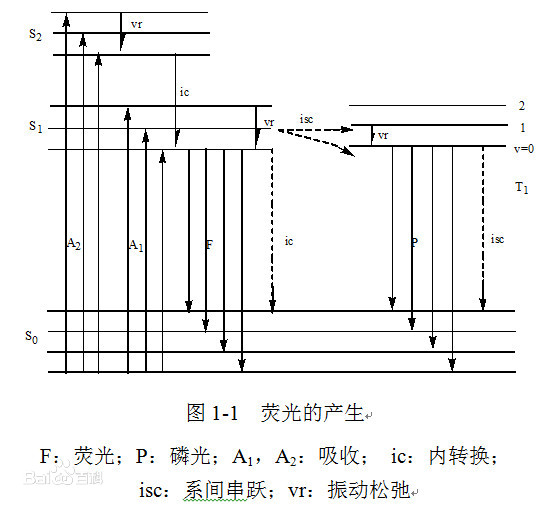

The principle behind fluorescence

When light shines on certain atoms, the energy of the light causes some electrons surrounding the atomic nucleus to jump from their original orbits to higher-energy orbits—transitioning from the ground state to the first excited singlet state or the second excited singlet state, and so forth. Since the first excited singlet state or the second excited singlet state are unstable, they eventually return to the ground state. As the electrons fall back from the first excited singlet state to the ground state, the excess energy is released in the form of light, thus producing fluorescence.

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance after it has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength and lower energy than the absorbed light. However, when the absorption intensity is sufficiently high, two-photon absorption may occur, leading to emitted radiation with a shorter wavelength than the absorbed light. When the wavelength of the emitted radiation matches that of the absorbed light, this phenomenon is known as resonant fluorescence. A common example is the absorption of ultraviolet light by a substance, which then emits visible-light fluorescence. The fluorescent lamps we use in everyday life operate on this principle: the phosphor coating inside the lamp tube absorbs the ultraviolet light emitted by the mercury vapor within the tube and subsequently re-emits visible light, making it visible to the human eye.

Fluorescence parameters

(1) Excitation Spectrum: The relationship between the intensity or luminescence efficiency of a specific emission line or band of a luminescent material and the wavelength of the excitation light under illumination by light of different wavelengths.

(2) Emission Spectrum: The variation in the intensity of luminescence at different wavelengths when a luminescent material is excited by a specific excitation light.

(3) Fluorescence Intensity: The fluorescence intensity is related to factors such as the fluorescence quantum yield, extinction coefficient, and concentration of the substance.

(4) Fluorescence quantum yield Q: The quantum yield represents a substance's ability to convert absorbed light energy into fluorescence; it is the ratio of the number of photons emitted by a fluorescent substance to the number of photons absorbed.

(5) Stokes shift: The Stokes shift is the difference between the wavelength of maximum fluorescence emission and the wavelength of maximum absorption.

(6) Fluorescence lifetime: When a beam of light excites a fluorescent substance, the molecules of the fluorescent material absorb energy and transition from the ground state to an excited state. They then emit fluorescence in the form of radiation as they return to the ground state. The fluorescence lifetime is defined as the time required for the fluorescence intensity of the molecules to decrease to 1/e of its maximum intensity at the moment when excitation ceases.

Cadmium selenide quantum dots emit fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet light.

Applications of fluorescence

Lighting

Fluorescent lamp

A common fluorescent lamp is a prime example. The inside of the lamp tube is evacuated and then filled with a small amount of mercury. When an electric discharge occurs between the electrodes inside the tube, the mercury emits light in the ultraviolet spectrum. This ultraviolet light is invisible and harmful to human health. Therefore, the inner surface of the lamp tube is coated with a substance called phosphor (or fluorescent material), which absorbs the ultraviolet light and re-emits it as visible light.

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) that can emit white light also operate on a similar principle. The light emitted by semiconductors is blue, and this blue light can excite phosphors—such as phosphorus—attached to the reflective electrode, causing them to emit orange fluorescence. When these two colors of light are mixed together, they approximate white light.

Highlighter

Highlighters contain fluorescent dyes that produce a fluorescent effect when exposed to ultraviolet light—such as sunlight, daylight lamps, or mercury lamps. Under UV illumination, these highlighters emit white light, giving the colors a striking, fluorescent appearance. The fluorescence of highlighters differs from that of watches or glow sticks: glow sticks rely on an internal radioactive reaction that generates radiation, which in turn excites the surrounding fluorescent powder to emit light. As a result, glow sticks can continue to glow even in the absence of any UV light at night. In contrast, highlighters only exhibit fluorescence when exposed to UV light. You can easily verify this by holding the highlighter’s mark close to a mosquito trap or a banknote detector—both of which emit UV light.

Biochemical and medical

Fluorescence has wide-ranging applications in the fields of biochemistry and medicine. By means of chemical reactions, fluorescent chemical groups can be attached to biomolecules, and then these biomolecules can be sensitively detected by observing the fluorescence emitted by the labeled groups.

DNA sequencing profile obtained using a fluorescently labeled chain-terminating agent.

The chain-termination method for automated DNA sequencing: In the original method, the primer ends of DNA had to be labeled with fluorescent dyes to enable precise identification of DNA bands on the sequencing gel. In the improved method, the four types of dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs)—which serve as chain terminators—are each individually labeled with fluorescent dyes. After electrophoresis, DNA molecules of different lengths separate according to their sizes. Upon exposure to ultraviolet light, the four differently labeled dideoxynucleotides emit fluorescence at distinct wavelengths. By analyzing the fluorescence spectrum, the DNA sequence can be accurately determined. DNA detection: Ethidium bromide is a fluorescent dye that emits only very weak fluorescence when it freely changes its conformation in solution. However, once it intercalates between base pairs in the double helix of nucleic acids and binds to DNA molecules, it produces intense fluorescence. Therefore, ethidium bromide is commonly added during gel electrophoresis to stain DNA. DNA microarrays (biochips): Genomic probes must be labeled with fluorescent dyes, and the target sequences are ultimately identified by analyzing the resulting fluorescent signals. Immunofluorescence assay in immunology: Antibodies are labeled with fluorescent dyes, allowing researchers to determine the location and nature of antigens based on the distribution and morphology of the fluorescence. Flow cytometry (also known as fluorescence-activated cell sorting, FACS): Sample cells are labeled with fluorescent dyes, then excited by laser beams to produce specific fluorescence. The emitted fluorescence is detected by an optical system and transmitted to a computer for analysis, thereby revealing various characteristics of the cells. Fluorescence technology is also applied to detect and analyze the molecular structures of DNA and proteins, especially those of complex biological macromolecules. The jellyfish luminescent protein was first isolated from the marine organism Aequorea victoria. When coexisting with calcium ions, it emits green fluorescence. This property has been utilized to observe in real time the movement of calcium ions within cells. The discovery of the jellyfish luminescent protein spurred further research on marine jellyfish and led to the identification of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). The polypeptide chain of GFP contains a unique chromophore structure that allows it to emit stable green fluorescence upon exposure to ultraviolet light without requiring any additional cofactors or special treatments. As a result, GFP and related proteins have become essential tools in biochemical and cellular biology research. Fluorescence microscopy: Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy—many biomolecules possess intrinsic fluorescence and can emit fluorescence without the need for additional chemical groups. Sometimes, this intrinsic fluorescence can change in response to environmental conditions, making it possible to use such fluorescence sensitivity to the environment to detect the distribution and properties of molecules. For example, bilirubin, when bound to a specific site on serum albumin, emits strong fluorescence. Similarly, when red blood cells lack iron or contain lead, they produce zinc protoporphyrin instead of normal heme (hemoglobin); zinc protoporphyrin exhibits intense fluorescence and can thus be used to help identify the underlying cause of certain diseases.

Gems, minerals

Gems, minerals, fibers, and other materials that can serve as forensic evidence may emit fluorescence of varying characteristics when exposed to ultraviolet or X-ray radiation.

Rubies, emeralds, and diamonds can emit red fluorescence under short-wavelength ultraviolet light. Emeralds, topaz (yellow jade), and pearls can also fluoresce under ultraviolet light. Additionally, diamonds can exhibit phosphorescence under X-rays.

Conceptual distinction

Luminescence induced by excitation from light (typically ultraviolet or X-rays) is called photoluminescence, which includes phenomena such as fluorescence and phosphorescence. Luminescence caused by chemical reactions is known as chemiluminescence; the fluorescent sticks used at concerts emit light through a chemical reaction triggered by the mixing of two liquid chemicals. Luminescence induced by cathode rays (a beam of high-energy electrons) is called cathodoluminescence—this is precisely how the fluorescent screen in a television’s cathode-ray tube emits light. The phenomenon of cold luminescence in living organisms is called bioluminescence; for example, the light emitted by fireflies is referred to as “yingguang.” In ancient Chinese, the character “ying” was used interchangeably with “ying,” and in some Chinese-speaking regions, the character “ying” is specifically associated with insects. In Taiwan, fluorescence is often referred to as “yingguang”; on the Chinese mainland, it is more commonly called “yingguang,” whereas “yingguang” typically refers specifically to the light emitted by fireflies.

Instrument

Fluorescence measurement absolutely requires an instrument. The instrument commonly used to detect the amount of fluorescence contained in a substance is called a fluorescence spectrophotometer.

The basic structure of a fluorescence analyzer includes: an excitation light source, an excitation monochromator, a sample chamber, an emission monochromator, and a detection system.

Previous page

Next page

Previous page

Next page